"Aurora borealis!? At this time of year, at this time of day, in this part of the country, localized entirely within your kitchen!?" – Superintendent Chalmers

I think we’ve all seen this scene in The Simpsons, and if you haven’t then make sure you do watch it as it is a fan fave. Aurora borealis, more commonly known as the northern lights, is the big shiny cosmic display of colors that happens in the northern reaches of the planet. Fun fact: in the southern hemisphere the same light display does happen but is called Aurora Australis, and the general name for both the northern and southern lights is Aurora Polaris. Many people have “See the northern lights” on their bucket list, fewer actually go out to hunt them, and even fewer yet succeed. That being said, they are not exactly elusive and in this post I’ll try to give you a run down of some tips and general knowhow that will help you check off one more item from your list.

Location, location, location

The northern lights are called thusly because they occur in the northern reaches of the planet. Let’s back up for a very quick re-cap of what the northern lights actually are, courtesy of the Library of Congress website:

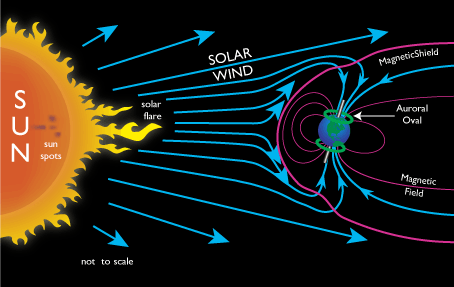

The origin of the aurora begins on the surface of the sun when solar activity ejects a cloud of gas. Scientists call this a coronal mass ejection (CME). If one of these reaches earth, taking about 2 to 3 days, it collides with the Earth’s magnetic field. This field is invisible, and if you could see its shape, it would make Earth look like a comet with a long magnetic ‘tail’ stretching a million miles behind Earth in the opposite direction of the sun.

When a coronal mass ejection collides with the magnetic field, it causes complex changes to happen to the magnetic tail region. These changes generate currents of charged particles, which then flow along lines of magnetic force into the Polar Regions. These particles are boosted in energy in Earth’s upper atmosphere, and when they collide with oxygen and nitrogen atoms, they produce dazzling auroral light.

– Library of Congress

There are a few things worth nothing from this explanation. Firstly, auroras have more to do with the sun’s occasional increased solar activity than anything to do with the Earth. Secondly, the “Earth” part of this equation has to do only with the ever-present magnetic field, which does not change its activity due to seasons or factors you’d be able to see on a human scale. Finally, since the ionized particles flow along the lines of the magnetic field, it makes sense that they’d be visible around where that magnetic field intersects the atmosphere rather than where that magnetic field is in the vacuum of space. Take a look at this diagram from Service Aurora:

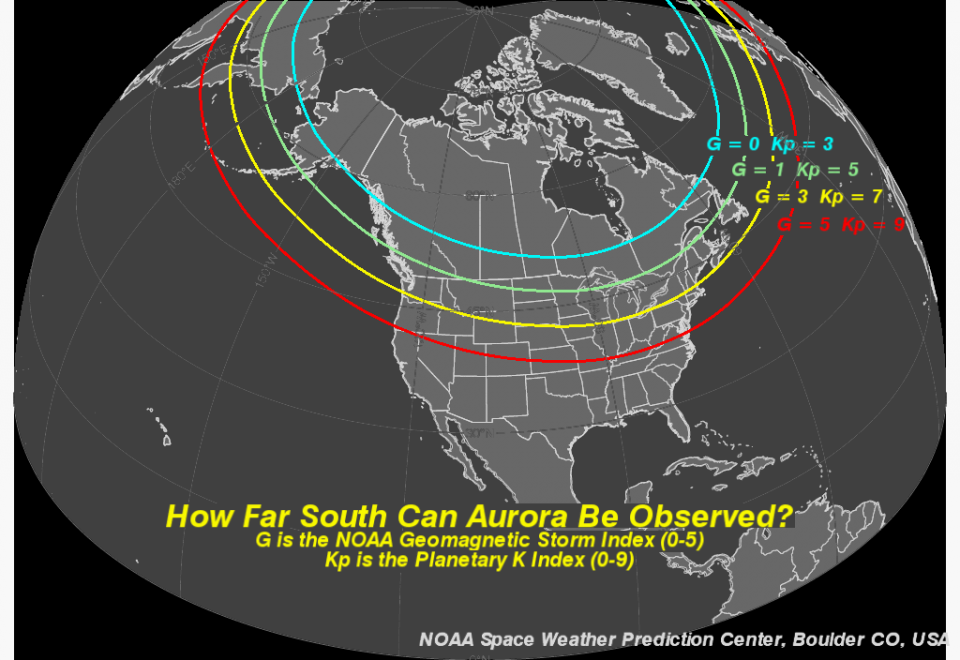

So the closer you go towards the north or south poles, the better your vantage point if the solar activity strikes Earth. How far is north “enough”? Well, apparently it is not uncommon to see the aurora as far south as Manitoulin Island in Ontario which is only about a six hour drive from Toronto - easily doable for a weekend road-trip getaway. Here’s a map that shows the “KP” levels (which are a measure of magnetic activity) for various latitudes. The lower the KP number, the more your odds of seeing the aurora.

Winter is coming

We’ve long heard about Iceland being a fantastic travel destination that is on the bucketlist for many a fellow traveller. Whether you are into ethereal waterfalls, rugged ocean-side cliffs, or otherworldly ice caves, there’s lots to see in Iceland. Then one day we noticed a deal from TravelZoo that seemed too good to pass up - $600 CAD for a flight and hotel combo in Reykjavik. The thing is, at least part of the reason why it was so cheap was because the available dates were during the middle of the winter. We debated if it’s worth going but among the biggest “pros” of going to Iceland in the winter was the high chance of seeing the northern lights. So in January 2016 we booked our tickets for the middle of February, packed our bags, and off we went.

So why does it matter if it’s winter or not? If the sole variable that affects whether our atmosphere is ionized depends on whether or not the Sun farts into space then why would the seasons change anything? Well, the truth is that it doesn’t - CMEs happen regardless of our seasons, but the problem is that if the air is ionized during daytime, the bright light of the Sun will completely drown out the aurora and make it invisible to the human eye. You know when there’s generally less sunlight around? That’s right… during winter! So trying to view the aurora during the long winter nights gives you more chances (more hours in a 24 hour period) to see it.

Your eyes versus a camera

“Whatever it is you’re seeking won’t come in the form you’re expecting.” – Haruki Marukami

A final thing to note on observing the auroras is that those beautiful shots you see with vivid colors dancing in the air are not what you’re going to experience in person. Those shots unsurprisingly use long shutter times, sensitive camera lenses, and various other tools to achieve the results you see. In reality, auroras generally move pretty slow and are not as colorful as those videos and photos may have you believe. To quote this Huff Post article that summarizes this pretty well:

If you’re lucky, you might see faint glows of green, light purple or pink, and only in rare cases do viewers report bright, multicolored light shows. No matter what you see outside, the real northern lights are not like what you see in photos.

One more thing: Check the forecast

As I mentioned earlier, the only factor that affects whether or not the aurora even happens is based on solar activity. To this end, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration maintains a website that has a solar activity forecast which can help you see the forecast of what’s happening on the surface of the sun. Use it to your advantage.

Another factor that affects if you can see the auroras are clouds - since they generally sit between you and the ionized air, they block the view of the lights so remember to check the weather forecast in addition to the solar one.

So what can I expect?

Well, when we went we were lucky enough to have a clear night with a little bit of a light show.

Admittedly, in person it looked more like a white cloud and was more faint. Happy hunting!